As a mental health advocate, and a sensitive human being, I have wanted to do more to help the Palestinian people, but I’ve found myself feeling inadequate and powerless – beating myself up over not doing more already and letting that push me into further inaction. The problems in the world can feel overwhelming; it is in those moments I believe we need to find more power to lean into love and lean into hope. We’re all just one person; it’s together that we make a difference, cliche as that may be. So I decided to do what I can and write something here, because this is my little space. If we all do what we can I have a sneaking suspicion we might make a whole lot of difference, even if waiting to see that materialise can be heartbreaking.

Why do I care about Palestine? Because I care about people. We are watching horrific crimes against humanity, what the International Court of Justice has plausibly called a genocide, live streamed to us in real time following what the United Nations has recognised as a 76 year apartheid campaign in Palestine. That’s not normal. And it should never be normal or acceptable. I know personally I have become emotionally numbed to the every day experience of the images and reports streaming in. If that is you too, I implore you not to let that numb, crisis-responding brain to stop you from caring and taking action. It is more than understandable that we are having intense and varied reactions to the violence, but that doesn’t strip our humanity, in fact it shows it.

I believe all of our struggles are interconnected, and that this interconnectedness impacts us in ways we are often unaware of. From the viewpoint of a mental health advocate, my heart breaks for the grief weaving between the Palestinian people. Losing homes, family, children, their dreams, their land… the list goes on and on. How can anyone process that grief and that pain? How can we allow people to go on living in such unimaginable fear and suffering, constantly? Not only their lives and legacies are being attacked, but also their joy.

Yet I have seen such incredible displays of resilience and joy and community from Gaza. Using music, dance, art, magic shows and an ongoing commitment to educating their children in the most horrific circumstances. This is what inspires me to keep hoping and pushing for them, because it gives a glimpse of the resilience of the human spirit and the possibility for future world building.

As a mental health advocate I think often too of the neurodiverse adults and children in Gaza. How the constant uncertainty, unexpected changes, loss of familiarity, and noise from bombings and the 24/7 drones must be affecting them. I can’t deal with a humming fan for a few minutes before I start to become distressed – how is this mental torture going to affect them long term? How much more likely are they to die?

As Maysoon Zayid said, what’s happening in Palestine is a ‘mass disabling event’. We do not currently have the infrastructural setup pretty much anywhere to comprehend or deal with disability on such a scale. The genocide in Palestine highlights many issues with how we conceptualise mental illness, distress, and disability. In the west we use a highly individualised model that tends to view the mentally ill or disabled person as the problem without true consideration of what makes the person disabled, the structural problems, or how we decide distress is illness. As a mental health advocate, I hope what we see in Palestine can inspire us also to reconsider how we decide someone is ill, and how we provide support. Maybe it’s inconsequential to bring up while people are still actively being killed – but the possibility to find multiple avenues of change in these horrors keeps me energised to carry on trying.

As Dr Samah Jabr, Palestine’s head of mental health services said in 2019, ‘I question the methodology. I think they’re measuring social psychological pain and social suffering, and they’re saying this is depression. What is sick, the context or the person? In Palestine, we see many people whose symptoms – unusual emotional reaction or behaviours – are a normal reaction to a pathogenic context. There are many people in Palestine who are suffering. But Western-developed tools for measuring depression, such as the Beck inventory, do not tend to distinguish between justified misery and clinical depression’. She raises important questions around the way we conceptualise trauma and mental health for Palestinians, and indeed the world. We only grow by continuing to reconsider what we know.

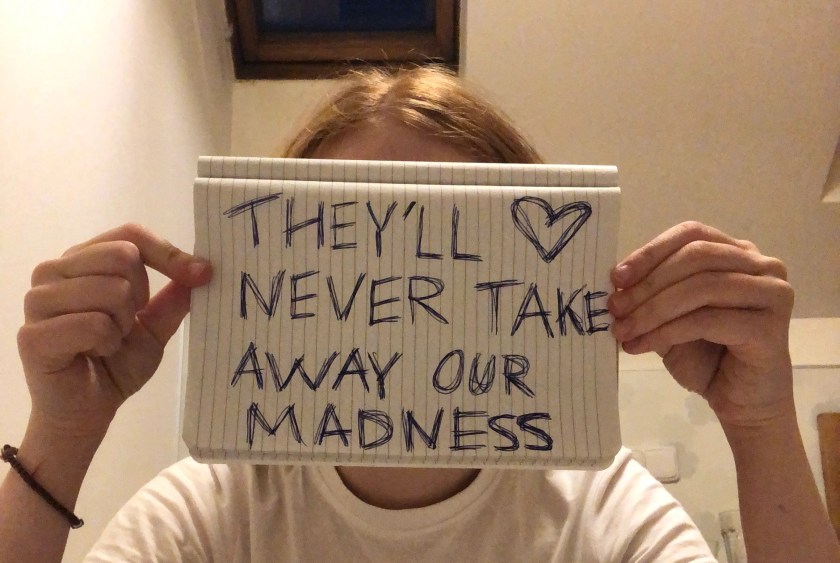

All this to say, we need to do something. I am first and foremost a creative and a mental health advocate. So I can raise my unique voice by writing things like this, that take a look at the situation through the lens of a mental health advocate. How can you use your unique voice? I encourage you to ask that question. And remember, it’s never ever too late to do something to help someone else in this world – never let anyone shame you for not doing what you didn’t yet know you could. We only have today, so let’s make it count.

Below are some ideas I’ve gathered on how to help the Palestinian people, and a few resources, because education is the most powerful tool we have. I don’t have a grip on the whole situation or the history, and frankly I have no idea what the best solution would be in the intricacies of international law and politics. Bottom line, what I do know is: anti-zionism is NOT anti-semitism, and the killing has to stop. We have to fight for peace.

How you can help & resources:

- BDS (Boycott, Divestment, & Sanctions) – A Palestinian-led movement that helps you know what to boycott to make an impact with what money you do/don’t spend. They have different catagories for the type of boycotts and links to other organisations supporting Palestine in your country. You can find their website here

- Protests – Protests supporting Palestine have been taking place across the world, and they have done a huge amount to raise moral, momentum, awareness, and make change. In the UK the next National Demonstration calling for a ceasefire is taking place in London at 12 noon on the 18th. You can find more information about this and other events in the UK here. I have been to the protests in London and they are incredibly inspiring and joyful – people of all ages, faiths and nationalities have been in attendance. If you can go I would really encourage you to show your face!

- Read! – It’s so important we take time to educate ourselves properly on this issue and learn more about the world around us. There are many ways to do this and if reading feels like an impossible task right now, don’t worry! It’s all about doing what you can. Watching some videos, like Bisan’s online series, or some articles are a great way to start. But reading is powerful; from books we get an almost unrivalled depth of knowledge and undertsanding. Here is a list of books to start your search, it is split into several categories

- Podcasts – Podcasts can also be a great way to learn about Palestine as you go through your day. If you have been trying to make sense of the media portrayal of the Palestinian solidarity, and specifically the student encampments that are popping up currently, I would really recommend this episode of queer, Jewish creator Matt Bernstein’s ‘A Bit Fruity’. It’s a good listen for people with in depth and less knowledge of the pro-Palestinian movement alike

- Follow Palestinian journalists, artists, and organisations – I love Bisan (@bisan_wizard1 on Instagram) in particular, and the Palestinian Solidarity Campaign in the UK is a great way to find out about events and other people to follow

- Petition your government – Attend events lobbying MPs in person, write to your representatives regularly, and sign petitions like this one (and google others lobbying your government!)

- Donate to UNRWA – Let’s be completely clear that the work UNRWA does to support and feed the Palestinian people is vital. As more aid agencies have pulled out of Gaza due to unprecedented danger for their workers, the support UNRWA provides has become even more crucial. Israel made false allegations that UNRWA workers aided in the October 7th attack – there is no evidence for this. Without their aid, even more Palestinian people will die from starvation. You can donate to help their life saving work here

- Donate directly to Gazan families – Many families in Gaza have started Gofundme pages to raise enough money to help them flee, pay for crossing the border, and setting up new lives elsewhere. Here are just a few you can donate to if you have some spare cash: Ghabayen family, family with 3 disabled children from Gaza (this one has very few donations so needs a lot of help!

- Look after yourself – find ways to connect with yourself in this troubling time; to lean into love and its regenerative power. When was the last time you danced, connected with your body? Have you ever felt a connection to nature, and how can you foster that connection to the earth? Can you reach out and build community (the solidarity movement is so open and a great place to find kind souls to connect with)? What has helped you before? If you are troubled, maybe this can be part of our collective world building and joy growing. I dunno, just an idea

- Keep questioning and learning and discovering for yourself

- Be creative – art is powerful and creative thinking is powerful. Use your voice and dream up new ways and remix old ways and be creative in how you can make a difference!

I thought I’d end the post with a poem by Refaat Alareer, who lost his life in this onslaught:

If I Must Die

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze—

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself—

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

فال بد أن تعيش أنت

رفعت العرعير

إذا كان لا بد أن أموت

فال بد أن تعيش أنت

لتروي حكايتي

لتبيع أشيائي

وتشتري قطعة قماش

وخيوطا

(فلتكن بيضاء وبذيل طويل)

كي يبصر طفل في مكان ما من ّغّزة

وهو يح ّّدق في السماء

منتظرًاً أباه الذي رحل فجأة

دون أن يودع أحدًاً

وال حتى لحمه

أو ذاته

يبصر الطائرة الورقّية

طائرتي الورقية التي صنعَتها أنت

تحّلق في الأعالي

ويظ ّّن للحظة أن هناك مالكًاً

يعيد الحب

إذا كان لا بد أن أموت

فليأ ِِت موتي باألمل

فليصبح حكاية

ترجمة سنان أنطون

Translation by Sinan Antoon

Sending all of my love and support to you today xx