Content warning: ED, psychiatric abuse, suicidal ideation, any mental health topic really

I want to write a really strong and defiant letter. I want to write some crazy, proud, creative theatre piece. I want to write something truly hopeful. And while I do have hope, and I do have gratitude – because it is essential to my survival – I also have a lot of pain. And anger. I can talk openly about so many traumas and just general shitty things that have happened in my life. But the one I’ve never been able to write about, never even been able to get through a conversation about without screaming and crying, is the pain endured under the psychiatric complex. Because they were meant to help me. Time and time and time again I have gone looking for help and time and time and time again I have been turned away with only more hurt. I know help is a brave word. I’m not afraid to say it. But I am afraid that when I say it no one will listen. This is my story of a journey through the mental health system.

Just a disclaimer, because as a writer on mental health I feel it is my responsibility – if you are in a bad place and looking for professional help, please do not use this as your excuse not to. I do know some people have been greatly helped by the mental health system, and you could be too. This is not intended to invalidate anyone’s good experiences, but rather to say that all of us deserve to have those good experiences. This is simply my story as someone who feels they have slipped through the cracks. If you feel this may affect you negatively I implore you to take the decision not to read any further.

I first asked for help from the mental health system when I was 12 years old. I was experiencing mood swings and distress that were really bothering me – maybe just normal teenage things, maybe not, but the point is it doesn’t matter. They were bothering me. Anyone who wants help, even just to navigate daily life, should be given it. I was assigned a counsellor from the early intervention team. I didn’t like them, so I asked to change. I was discharged from the service – I took that as a message that if I had an opinion on my care, my care would be withdrawn from me.

My first contact with CAHMS (child and adolescent mental health services) was due to an eating disorder at 14. My life was being ruled by it – I had complete meltdowns when I couldn’t exercise, was hyper fixated on food all the time, was weak and angry and alone; I was really hurting. They weighed me. They told me I wasn’t a low enough weight. I took that to mean I wasn’t sick enough. Without any regard for how I felt, or how food was ruling my life; without anyone trying to find out anything about my experience they denied me the help I so desperately needed. Suggested possibly a meal plan – with no support to implement it or formulate it. If a teacher hadn’t sat with me at lunch every single day for a year and coached me through it because she’d been there too, I don’t know how I would’ve gotten through it.

I severely relapsed with my eating behaviours twice more, and I still struggle with some thought patterns and triggers to this day (though I am in a much better place, largely due to recovery in other areas giving me the tools to transfer). But I never felt like I really recovered from it, or had the support I needed. Even 9 months ago that teacher would still notice when my old behaviours around food crept in – even before I did – and help me to recognise and head them off. I am immensely grateful for that… but it wasn’t her job. It was never her job to be the main guidance and support in eating disorder recovery.

CAHMS did offer me six sessions of group therapy. This was to deal with my overwhelming anxiety – much of it around socialising – and deep depression. They didn’t see it as deep depression. It was. It was really, really dark. I stopped going to any lessons and lost all sense of self and hope. But yeah, six sessions would be enough apparently (obviously not). I freaked out at the thought of group therapy, it was entirely unsuitable for me. Once again I received the message in response that if I had an opinion on my care, I wouldn’t get any care. They wanted to discharge me right then, but my wonderful mum stuck up for me so they offered me three – I repeat THREE – CBT sessions. They were not useful. I was put on a years long waiting list for an autism assessment. I was offered no more support. I continued to struggle.

My mum’s determination to get me the help I deserved was incredible, and probably the only reason I got any support at all. (My mum is probably reading this, so thanks mum). She found a charity that was amazing in supporting us through my teen years, and funded me to see a private psychiatrist – this would not have been possible without them. However I wouldn’t say that was particularly helpful either. That psychiatrist did diagnose me with autism (side note – the assessment for autism really needs to be changed), anxiety and depression. I am eternally grateful for my autism diagnosis – it truly did change my life knowing I was autistic. But it changed my life because I went away and learnt about it, as did my family. The psychiatrist did not formulate a treatment plan for any of this, or provide any further support. Some medication that didn’t work was all she offered.

In this time I also saw a few therapists – I didn’t like them, one of them didn’t like me and kinda dumped me. All of them were privately paid for. The subpar care I received was paid for privately – can you imagine how much worse it would have been if we hadn’t been able to afford it?

I know this is all a lot of information, but stick with me here. This journey is important to understand because it is something so so many people face. I slipped through the cracks of this system – even with the privilege of being a white, cisgendered woman. I had it reasonably easy.

In February 2020 I had what I now recognise to be my first (and most intense) mixed episode. I cannot even put this experience into words but essentially it was all the darkness of depression with all the heightened energy and irritability of mania at the same time. I felt reality slipping away from me and I have never been in such intense distress. Two teachers stayed with me at school hours after school ended to try and keep me safe. They eventually helped me calm down, but I later found out they were so concerned they were about to call an ambulance or the police, as the crisis line wasn’t helping. I went to the GP during this episode begging for help. She prescribed me valium to calm me down, but when I begged her for more support I remember her chastising me for being so emotional because she had other patients waiting. I took that as a message that I still wasn’t sick enough; still wasn’t important enough.

In March 2020 the private psychiatrist diagnosed me with cyclothymia. We had to pay extra for an emergency appointment. She decided I was now too complicated to be under her care and needed more support so referred me back into the NHS. They did not follow up on her recommendation for more support. By the time they saw me I was a bit calmer so apparently that meant I didn’t need help. In her eyes I was too bad, in their eyes I wasn’t bad enough. So I was left with nothing. This was the trend that would continue for the next three years.

In September 2020 I wound up in A&E. I was broken and desperate. When the CAHMS crisis person finally arrived she acted annoyed about me being there, annoyed she had to be there, uncaring. She essentially asked ‘if things are so bad then why haven’t you killed yourself yet?’ and sent me home with no support. They didn’t follow up on any support because I calmed down a bit after, so I was no longer considered in crisis when they finally did get in contact (even though they hadn’t helped me when I was in crisis) and because I was drinking at the time. Just so we are all clear – if a young person is drinking as heavily as I was, that is exactly the time they need support. I went to my first AA meeting after I left the hospital that day. And excuse my french but thank fuck I did. I have no idea if I would still be alive otherwise. And having connected with others who have been subjected to inpatient treatment, I am incredibly grateful I did not have to bear that extra trauma. This is how bad the surface level service is – it’s even worse inside.

After I got sober in July 2021 I was still struggling. I finally got to see a psychiatrist on the NHS in October 2021 because of my mum’s insistent fighting for me. When he asked me what I wanted from the meeting, he chastised my response. He was unclear. He shouted at me, and revoked what I thought I had been diagnosed with in a letter. I was meant to see him again in 10 weeks and he cancelled. I got discharged from CAHMS without them ever asking to talk with me about how I was doing.

The one professional who has been a saving grace is my therapist. She is autistic herself and very flexible. But again – if I wasn’t able to fund that privately I don’t know where I would be. After my charity funding stopped when I turned 18 I had to take the sessions down to every 2 weeks, even with her sliding scale, which is significantly less helpful. Luckily I’ve also found amazing peer support, especially through AA, and spent a lot of time reflecting and doing my own work, so I’ve managed to build myself a much brighter life. But it’s been hard. And sometimes I really do need some more help – no one should have to do this alone.

I Went back to the NHS this October and had my first ever good meeting with anyone, just someone in my GP clinic. Why? He was honest. He genuinely seemed to care, but there was nothing they could offer me. He explained that as far as the system saw it, I had already been helped.

In late 2022 my mental health really started to decline again. I went back to the NHS this October and had my first ever good meeting with anyone, just someone in my GP clinic. Why? He was honest. He genuinely seemed to care, but there was nothing they could offer me. He explained that as far as the system saw it, I had already been helped. So from October I was searching for a psychiatrist who would see me.

I was turned down by over 10 private psychiatrists for being too complex, having comorbidities, or my favourite way of putting it: ‘them not being able to offer the support I need at that time’. So I was again too bad for private and not bad enough for the NHS. One of the only people who would see me charged just under £1000 a session. Others said they would consider seeing me, but were booked up until 2024.

Finally in March 2023 – 5 months later – I got to meet with a private psychiatrist. And wow, he was amazing. We had three meetings so we could cover everything. He was kind, listened to me – really listened – and didn’t patronise. He treated me like an adult, and made it clear I would have a say in my care plan and the final report that would be sent to my doctor. I would have a say? I almost thought that wasn’t allowed. I’m still sceptical, it still doesn’t feel real.

He diagnosed me with Bipolar type 1. Just think about that for a minute – an 18 year old has been dealing with undiagnosed bipolar 1, unsupported, emerging from 12 years old. I have no idea where I would be without the angels placed in my life along the way; without the undying support of my family and friends; without the flexibility of my school. I knew something more was going on, I knew how much pain I was in, and no one in the mental health industry was listening. I was screaming into a void and not even hearing the echoes of my own screams. (A separate issue is that we shouldn’t need labels to validate that level of human distress, which is what it is at its core, but diagnosis can be so validating. Read more about that here).

I am not in any way saying this one experience erases all the rest. It does not. It absolutely does not. And it doesn’t not mean that psychiatry isn’t built on an oppressive, harmful foundation whose history has been hidden. It is. But it was a little hope given back to me. A relief at the very least. Before I went into that meeting I said ‘I’ll take them just not being actively mean to me’. How sad is that? What a desperately low bar.

I’m still scared. He has instructed my GP to refer me back to secondary care teams in the NHS, which I still – like always – hope might offer some help. But the main thing offered seems to be medication, which I have some serious and valid concerns about. But I am terrified of raising these concerns or asking about alternatives for fear that a) I will be labelled as disordered and my new diagnosis weaponised against me or b) I will be labelled as non-compliant/ not wanting help enough, and sent away again. I wish I didn’t want help from them, and maybe one day I’ll be able to find a path that avoids dealing with the mental health system altogether. But I’m not there yet. Nor should I have to avoid it. It should be an inclusive, varied, accessible service. It should have community and individualised care. It should have alternative treatments and input from patients. It should see the human condition as a spectrum. But it doesn’t. And being mentally ill makes me scared that if I voice any of this, I will not be taken seriously. How can anyone ever prove that they are sane?

I deserve better. Everyone deserves better; we deserve to know that no matter what we’re going through there will be appropriate support for us. But it’s not there. And this broken system is quite literally killing people. We can’t just say fund the system either, the system needs to change. I need it to change, we all need it to change.

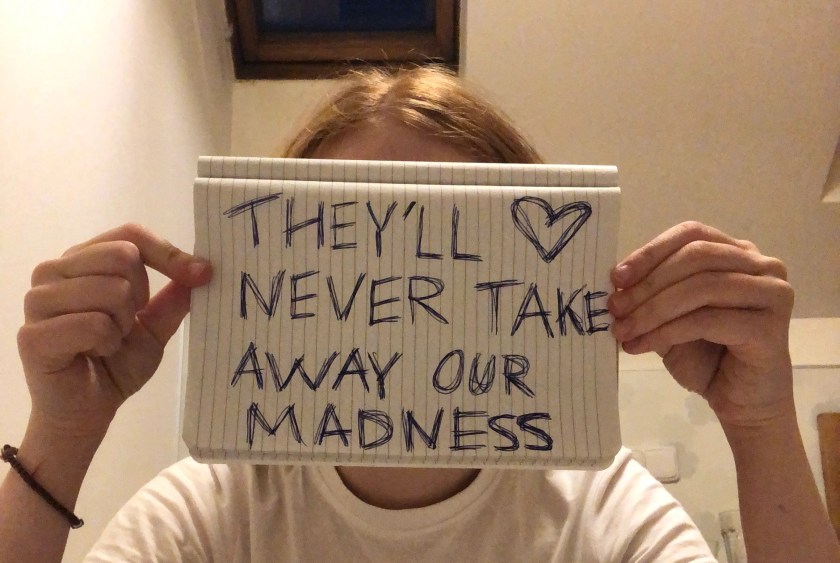

I think I’m sharing this because the younger version of me wanted desperately to read it from someone else. So the core message is that you are not alone. You are not alone in the hurt psychiatry has caused you. You are allowed to be angry about it, and distrusting of it. You are allowed to choose your own care and your own path – even if others don’t understand it! (And that applies to all paths – mental illness should not be policed). Your pain is valid, completely valid, and I see you. I see you.

Sending love and support to you all today xx